docs

Cosmology reference sheet

Angular wavenumber to comoving size

One often needs to convert multipoles to comoving sizes R or comoving wavenumber k (or back).

An angular multipole corresponds to some angle on the sky. The correct way to convert a multipole to an angle on the sky is

ell = pi / theta

This is correct both in the large scale and small scale limit. ell=1 corresponds to a dipole on the full sky, and the angular scale is then a 180 degrees on the sky. In the small-scale limit, the discrete fourier transform (under the flat-sky approximation) of a grid with pixel size theta radians has a maximum/Nyquist frequency of ell (e.g. ell~20,000 for 0.5 arcminute pixels).

To convert theta to some physical size some cosmological distance away, we use

Rp = dA(z) * theta

where Rp is the physical size of the object (in Mpc) and dA is the angular diameter distance. Often however, one works with comoving sizes. For a universe with zero curvature then

a Rc = a chi(z) * theta

and

Rc = chi * theta

Once we have the comoving size, we can simply take its reciprocal to get the comoving wavenumber k (up to factors of pi).

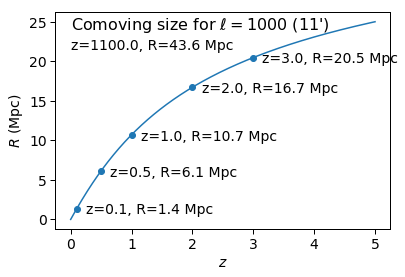

Everything above scales linearly or 1/linearly except for chi(z). So, once you know the R corresponding to a particular ell for a few redshifts, you can do everything else in your head for those redshifts. Below is a plot of the comoving size R corresponding to multipole ell=1000 for a few redshifts of interest.

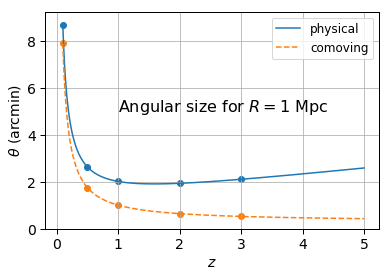

One can use the same relations to ask what angle on the sky theta an object of size R should subtend. The answer depends on whether we mean physical or comoving size. Interestingly, an object of fixed physical size doesn’t simply get smaller as you put it farther away from us (or at larger redshifts). There is a turnaround at z=1 ; because of the expansion of the universe, objects of the same physical size at higher redshift actually appear larger on the sky above z=1 !